How the Falklands War began

Today marks 40 years since the invasion of the British overseas territory in the South Atlantic

This weekend is the 40th anniversary of the invasion and occupation of the Falkland Islands by Argentina, sparking a ten-week war that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of British and Argentine military personnel.

As remembrance ceremonies take place between 4 May and 14 June, the island’s population of just 3,000 will be “swelled” by hundreds of veterans, as they gather to remember the lives lost in the 74-day war, says The Times. Unlike the First and Second World Wars, the Falklands is still “living history”, said the paper.

More than 25,948 UK Armed Forces personnel were part of the task force sent to the Falklands after Argentina invaded on 2 April 1982 and 255 died during the campaign to liberate the islands, said the Falkland Island’s government website. Three civilian islanders also lost their lives.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Falkland Islands have named this “special” commemorative year “Looking Forward at Forty”, marking it as “a time to reflect on the achievements that have been made with our hard-won freedom, and to look forward to the next 40 years of life in the Falkland Islands”.

How did the Falklands War start?

Sovereignty over the windswept and sparsely populated islands, situated off the coast of Argentina in the South Atlantic, was a source of tension for decades.

Britain has ruled the Falklands uninterrupted since the mid-19th century and the vast majority of the island’s tiny population - fewer than 3,000 at the 2012 census - are descendants of British settlers.

However, in Argentina, where the islands are known as Las Malvinas, the government says the country inherited control of them from Spain in the 1800s and points to their proximity to South America to bolster its claim of sovereignty.

In 1982, Argentina’s ruling military junta was facing an economic crisis and General Leopoldo Galtieri hoped an invasion would bolster his fading popularity at home.

Tension first started to boil over when a group of Argentine scrap metal-workers landed on British-controlled South Georgia, 810 miles east of the Falklands, on 19 March and raised the Argentinian flag.

Then, on 2 April, around 3,000 Argentine special forces invaded Port Stanley, the islands’ capital, setting the scene for conflict.

Did Argentina expect the UK to go to war?

The invasion of Port Stanley caught Whitehall off-guard. Six months earlier, UK intelligence had concluded privately that “the Argentine government would prefer to pursue their sovereignty claim by peaceful means”, said The Independent.

Thatcher’s government also sent out a signal that Britain had no wish to fight over the islands by scrapping the only British warship in their vicinity, HMS Endurance, in January 1982.

A now-declassified CIA document entitled “Solutions to the Falklands crisis” showed it believed the UK was “prepared” to accept the “ultimate turnover of the islands to Argentinian sovereignty”.

It also suggested that islanders who did not wish to become Argentinian citizens could be relocated to Scotland, the Daily Mail reported.

So why did the UK go to war over the islands?

Like her opposite number in Argentina, Thatcher was concerned about her popularity at home. Still in her first term, she was well behind in the polls and facing the twin threats of internal party dissent and the rise of the Social Democratic Party (SDP).

When she learned of the Port Stanley invasion, the prime minister took a “gamble” that war would boost her crumbling powerbase, said Simon Jenkins of The Guardian. Thatcher swiftly announced that the 1,800 islanders were “of British tradition and stock” and despatched a task force to journey 8,000 miles and reclaim the islands.

Although the war lasted only ten weeks, with the Argentinians sustaining far heavier casualties, British victory was a “desperately close” affair, Jenkins wrote.

“The conclusion of most defence analysts is that the Argentinians should have won this war, and had they awaited the south Atlantic storms of June they probably would have done.”

The sinking of the General Belgrano

The high command of the British Armed Forces made one of the most controversial decisions in its history when it ordered the General Belgrano to be torpedoed.

On 2 May 1982, in the middle of the war, the Royal Navy’s nuclear-powered submarine HMS Conqueror was given the order to sink the Argentine navy cruiser, an attack that resulted in the deaths of 323 sailors.

The sinking of the Belgrano was condemned by some observers as a war crime owing to the circumstances of the attack. Although the vessel had breached Britain’s 200-nautical-mile exclusion zone around the islands on 1 May, it left the next day and was sailing away from the Falklands when it was hit, The Telegraph said.

According to the UK Defence Journal, “during war, under international law, the heading and location of a belligerent naval vessel has no bearing on its status”, and the sinking was therefore technically legitimate.

Nevertheless, many critics, including some British commentators, see the sinking as a war crime to this day, said the Daily Mail.

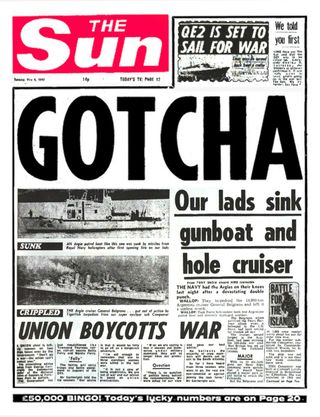

The controversy surrounding the sinking was compounded by The Sun publishing a front page featuring a photo of the Belgrano under the headline “Gotcha!”.

The Guardian reported that many were turned off by the paper “gleefully” reporting on the first deaths of the war, many of whom were in their teens, referring to editor Kelvin MacKenzie’s decision to publish the headline as “cold-blooded”.

The sinking of the General Belgrano remains a contentious and pivotal event in the course of the Falklands War.

What was the legacy of the war?

Thatcher’s apparent gamble paid off: the following year’s general election gave her the most decisive victory since that of Labour in 1945.

On a geopolitical level, the Falklands have remained firmly in British hands since 1982. In 2013, 99.8 per cent of islanders voted to remain part of the UK, with only three voting against.

However, tensions between the UK and Argentina bubbled between 2007 and 2015, under Argentine president Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who many critics accused of fanning the flames of the dispute to take the spotlight off her administration’s domestic shortcomings.

Her successor, Mauricio Macri, chose a less confrontational path. Although he upheld Argentine sovereignty over the islands in principle, he has remained relatively quiet on the subject and his administration saw a thawing of Argentina’s relations with the UK.

But tensions have been on the rise in recent months. In February, the current Argentine President Alberto Fernandez issued a joint statement alongside Chinese President Xi Jinping which stated that China “reaffirms its support for Argentina’s demand for the full exercise of sovereignty over the Malvinas Islands”. Foreign Secretary Liz Truss tweeted that the UK “completely” rejected “any questions over sovereignty of the Falklands”.

“The Falklands are part of the British family and we will defend their right to self-determination. China must respect the Falklands’ sovereignty,” she said.

As with any war, one of the lasting legacies for the soldiers who served in the conflict is the continued pain and trauma caused by long-term injuries.

Former soldier Simon Weston is one of the most well-known Falklands veterans.

He was on board the RFA Sir Galahad in Port Pleasant on 8 June 1982 when it was bombed and he suffered 46% burns.

The ship was carrying thousands of gallons of diesel and petrol as well as ammunition and phosphorus bombs. Out of Weston’s platoon of 30 men, 22 were killed.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Quiz of The Week: 13 - 19 April

Quiz of The Week: 13 - 19 AprilPuzzles and Quizzes Have you been paying attention to The Week's news?

By Rebecca Messina, The Week UK Published

-

'Colleges warn of punishment for disruptions'

'Colleges warn of punishment for disruptions'Today's Newspapers A roundup of the headlines from the US front pages

By The Week Staff Published

-

Peter Murrell: Sturgeon's husband charged over SNP 'embezzlement' claims

Peter Murrell: Sturgeon's husband charged over SNP 'embezzlement' claimsSpeed Read SNP expresses 'shock' as former chief executive rearrested in long-running investigation into claims of mishandled campaign funds

By Arion McNicoll, The Week UK Published