Why Finland won’t let go of the swastika

The symbol is still proudly displaced by the Finnish military, despite its Nazi associations

The swastika, a symbol most associate with the horrors of Nazi Germany, still adorns flags and military insignia in Finland.

Critics argue that the emblem should be consigned to the history books owing to its racist connotations, but the Finnish government has repeatedly rejected calls to restrict its use.

Where and why is it used?

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Finland has used the ancient symbol on monuments, awards and decorations for nearly a century, says the national broadcaster Yle.

The swastika, which is also a Hindu symbol of peace, was used by many in the West as a symbol of good luck during the early 20th century and was a common architectural motif in Finland during the 1920s and 1930s.

It was also favoured by Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela, who featured it on his designs for military insignia, including the Cross of Liberty.

The swastika is displayed on the flag of the president of Finland and appeared on Finnish Air Force planes until 1945.

“It had nothing to do with the Nazis, because we got it 1918, much before the Nazis ever existed,” says retired Lt Col Kai Mecklin, director of the Finnish Air Force Museum.

The swastika has “always been a symbol of independence and freedom” in Finland, he adds.

Should Finland stop using it?

Some see the persistence of the swastika in Finnish culture as problematic, “particularly with Finland situated between two regions for whom the swastika symbolises not freedom, but its Nazi opposite”, says The Christian Science Monitor’s Gordan Sander.

And as Finland’s far-right “becomes increasingly restive, it could force Finns to change the way they consider the symbol’s place in their modern society”, he adds.

Teivo Teivainen, professor of world politics at the University of Helsinki, says the authorities are quick to dismiss criticism of the military’s continued use of the swastika.

“When I talk to top politicians or people in the military about it, normally the response is that it has nothing to do with the swastika of the Nazis, it predates the swastika of the Nazis. End of conversation,” he says.

“To this day, I haven’t, found convincing arguments why using the swastika would be beneficial for Finland,” Teivainen adds. “I think the case for getting rid of the swastika is stronger than the case for keeping it.”

But former air force pilot Mecklin says banning the symbol would send the wrong message.

“If we now deny the use, or stop using the swastika, we could give a signal abroad that actually it was a Nazi symbol in Finland - which it never was,” he argues. “We are still proud of it and still using it.”

Meanwhile, the government remains opposed to even considering a ban. “At the present time, the Ministry of Defence has no plans to restrict or review the use of the swastika,” a military spokesperson said.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

'Republicans want to silence Israel's opponents'

'Republicans want to silence Israel's opponents'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Poland, Germany nab alleged anti-Ukraine spies

Poland, Germany nab alleged anti-Ukraine spiesSpeed Read A man was arrested over a supposed Russian plot to kill Ukrainian President Zelenskyy

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

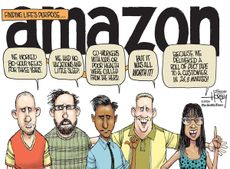

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - priority delivery, USPS on fire, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Puffed rice and yoga: inside the collapsed tunnel where Indian workers await rescue

Puffed rice and yoga: inside the collapsed tunnel where Indian workers await rescueSpeed Read Workers trapped in collapsed tunnel are suffering from dysentery and anxiety over their rescue

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

Gaza hospital blast: What the video evidence shows about who's to blame

Gaza hospital blast: What the video evidence shows about who's to blameSpeed Read Nobody wants to take responsibility for the deadly explosion in the courtyard of Gaza's al-Ahli Hospital. Roll the tape.

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Giraffe poo seized after woman wanted to use it to make a necklace

Giraffe poo seized after woman wanted to use it to make a necklaceTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Helicopter sound arouses crocodiles

Helicopter sound arouses crocodilesTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Woman sues Disney over 'injurious wedgie'

Woman sues Disney over 'injurious wedgie'Tall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Emotional support alligator turned away from baseball stadium

Emotional support alligator turned away from baseball stadiumTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Europe's oldest shoes found in Spanish caves

Europe's oldest shoes found in Spanish cavesTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Artworks stolen by Nazis returned to heirs of cabaret performer

Artworks stolen by Nazis returned to heirs of cabaret performerIt wasn't all bad Good news stories from the past seven days

By The Week Staff Published