What does the Taliban stand for?

Militants tell women to stay at home as radical overhaul gets underway

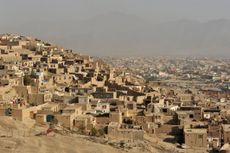

Women and girls in Afghanistan fear for their rights and safety now that the Taliban has taken control of the capital, Kabul.

In what Channel 4 News calls a “surreal” press conference beamed around the world yesterday, the militants said they will recognise women’s rights, including access to education and employment, within the “framework of Islam”. No violence or prejudice against women will be allowed, they said. “Women are going to be very active in our society.”

“What those promises mean in reality is far less clear,” says Channel 4. Many Afghans fear that women will see themselves stripped of the rights gained since the Taliban last ruled between 1996 and 2001, when they enforced a strict interpretation of sharia law that brutally repressed women.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As thousands of residents attempt to flee the country, the situation for women in Afghanistan is “terrifying”, writes Vrinda Narain, an associate professor from McGill University in Canada, for The Conversation. The militants’ promises have already been undermined by reports of “women and children being beaten and whipped” on the streets after trying to pass through checkpoints, says The Guardian.

Here are some of the changes that women may experience under the Taliban’s rule.

Return of the burqa

Under the previous Taliban regime failure to wear a burqa could result in severe punishment.

After the fall of the regime in 2001, women could choose whether they wanted to wear the garment. For some, shedding the burqa became “a symbol of a new dawn”, The Guardian reports, with women “able to dictate what they wore for themselves again”.

Now, for some women in Afghanistan, the garment “represents the sudden and devastating loss of rights gained over 20 years”, CNN reports. Many women have been wearing the head-to-toe covering again or shutting themselves in at home in fear and anticipation of new restrictions.

The Taliban has said its policy will be that women wear the hijab, a spokesperson has told the BBC, suggesting they might not have to cover their faces. However, both demand for burqas, and their price, have increased dramatically in the past 12 months, according to market sellers in Afghanistan’s capital. “As the fear among women in Kabul has grown, the prices have risen,” The Guardian explains.

Male ‘guardians’

Women were not allowed to leave their homes without a male relative, or “guardian”, during the previous Taliban regime. Since the insurgent group seized control of Kabul on Sunday, residents in some parts of the city have said that there are “no women walking on the streets”, The Guardian reports.

In July, Afghan news broadcaster Ariana News reported that the Taliban had allegedly told women in occupied areas that they could not leave their homes without a male guardian. A schoolteacher in the Takhar province has told the Associated Press that women have been instructed not to visit the local market alone.

Employment bans

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, women were unable to work under the Taliban regime. There are already reports that female employees have been replaced by male counterparts in some businesses. Writing in The Guardian, an anonymous Kabul resident said that her sister left her desk in a government office last weekend “with tearful eyes”, believing “it was the last day of my job”.

However, Taliban member Enamullah Samangani said yesterday that the regime “doesn’t want women to be victims”, adding that “they should be in the government structure according to sharia- law”.

The i newspaper reports that Afghan TV news stations “have resumed broadcasting with courageous female anchors” despite the Taliban takeover. But experts say the militants’ assurances so far are “nothing more than optics for the West”, says the newspaper. It notes that before 2001, women who broke the rules often “suffered humiliation and public beatings by the Taliban’s religious police, and sometimes death”.

Restrictions on education

Girls were not allowed to receive an education between 1996 and 2001. Pashtana Durrani, executive director of LEARN, a non-profit organisation focused on education in Afghanistan, told NPR that she believes the Taliban “will try to be very open to the idea of education”, but what kind of “educational rights” the regime will actually allow remain unclear.

Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen told Sky News that women will be permitted to be educated to university level and that “thousands” of schools remain open in Afghanistan. But a professor in Herat told the Financial Times that security guards outside the university where she works told her “women cannot go in for now”.

Women have in the past been persecuted by the Taliban for running informal lessons and study sessions in their homes. Many Afghans fear the worst, with teachers and students “grappling with what could be the end of education for generations of women and girls in Afghanistan”, Time reports.

Forced ‘marriages’ to Taliban fighters

A statement reportedly issued by the Taliban’s cultural commission last week called for religious leaders to provide the group with a list of girls over the age of 15 and widows under the age of 45 “to be married to Taliban fighters”, The Times of India says.

In The Conversation, Associate Professor Narain writes that “offering ‘wives’ is a strategy aimed at luring militants to join the Taliban”, but the union is a form of “sexual enslavement”. “Forcing women into sexual slavery under the guise of marriage is both a war crime and a crime against humanity,” she says.

Punishments

During the Taliban’s previous reign, “a woman could be flogged for showing an inch or two of skin under her full-body burqa, beaten for attempting to study, stoned to death if she was found guilty of adultery”, Amnesty International reported. There was also a case where women’s fingers were cut off as punishment for wearing nail varnish.

Associated Press reports that girls in the Takhar province last week were stopped and lashed for wearing “revealing sandals”.

The previous Taliban rule was “a bleak period for Afghan women” and while the years since have been ones of much suffering for the country, the treatment of women was at least one “widely recognized bright spot”, says The New York Times.

As the group’s claims that it has changed its ways are met with “deep skepticism”, the paper says the “question now is whether the Taliban’s interpretation of Islamic law will be as draconian as when the group last held power”.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

'A direct, protracted war with Israel is not something Iran is equipped to fight'

'A direct, protracted war with Israel is not something Iran is equipped to fight'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Today's political cartoons - April 17, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 17, 2024Cartoons Wednesday's cartoons - political anxiety, jury sorting hat, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Arid Gulf states hit with year's worth of rain

Arid Gulf states hit with year's worth of rainSpeed Read The historic flooding in Dubai is tied to climate change

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistan

The Taliban’s ‘unprecedented’ crackdown on opium poppy crops in Afghanistanfeature Cultivation in former poppy-growing heartland Helmand has been slashed from 120,000 hectares to less than 1,000

By Julia O'Driscoll Published

-

Dmitry Medvedev: Putin’s new ‘attack dog’

Dmitry Medvedev: Putin’s new ‘attack dog’Why Everyone’s Talking About The former Russian president’s rhetoric is becoming increasingly aggressive

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet Published

-

Taliban returns to ‘Stone Age Islamism’ in Afghanistan

Taliban returns to ‘Stone Age Islamism’ in Afghanistanfeature Taliban leaders view ‘complete gender segregation’ as a recipe for a ‘truly Islamic system’

By The Week Staff Published

-

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in Afghanistan

Taliban releases 2 Americans held in AfghanistanSpeed Read

By Catherine Garcia Published

-

Kim Philby: unmasking the original Cold War double agent

Kim Philby: unmasking the original Cold War double agentWhy Everyone’s Talking About New files reveal infamous Soviet spy could have been outed years before defecting

By The Week Staff Published

-

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchange

American detained in Afghanistan for over 2 years released in prisoner exchangeSpeed Read

By Theara Coleman Published

-

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawal

Afghanistan: A year after the withdrawalopinion What did the U.S. leave behind when it pulled out of Afghanistan?

By Grayson Quay Published

-

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombing

Prominent cleric who supported female education killed in Afghanistan bombingSpeed Read

By Harold Maass Published