Afghan War inquiry: generals owe us an explanation

There is no point in having armed forces that keep on getting beaten – however gallantly they performed

The Ministry of Defence looks set to announce an inquiry into the Afghan War once the final British troops leave the country next month. Such a process is absolutely vital to the future military efficiency of our armed forces who need to understand clearly the reasons for their defeat before they can regroup and reorganise.

I often wonder if at times our military leaders have sought to exaggerate to excuse. In an interview with the BBC on becoming Chief of the General Staff in 2009, General Sir David Richards described the fighting in Afghanistan thus: “This sort of thing hasn't really happened so consistently I don't think since the Korean War or the Second World War. This is persistent, low-level, dirty fighting." Others have loudly echoed his judgment.

Comparing the rigours and dangers faced by our troops in Afghanistan to the Second World War was completely absurd. Korea was a hyperbolic stretch as well.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Just to take one famous example: between 22-25 April 1951, during the battle of Imjin, 29 Infantry Brigade faced three divisions of Chinese and North Korean soldiers and suffered more than a thousand casualties killed, wounded and missing. The ‘Glorious Glosters’ alone lost 63 dead and 150-plus wounded, with a further 34 dying later in hideous North Korean prisoner-of-war camps. No casualty evacuation was possible and in the final desperate stages of the battle the only fire support available was from a battery of Royal Artillery 4.5in mortars.

Chinese casualties in the action are difficult to estimate but most authorities would accept a figure of 10,000 killed and wounded.

A much truer comparison would be to the British experience during the Malayan Emergency of 1948-60 (340 British military deaths) or the 1955-59 campaign against EOKA in Cyprus (371 British military deaths). Yet, curiously, Richards – a highly educated man – chose to ignore these two (ultimately successful) campaigns, instead reaching further back into the past to compare a failing Afghan counter-insurgency campaign with two general wars against conventionally armed opponents.

We beat the Malayan Communists and we beat EOKA. The Taliban beat us. Implicitly comparing them to the Wehrmacht or the Chinese People’s Army obviously makes defeat more palatable, more excusable. But it is as sly a piece of spin as I have ever seen.

We should also remember that compared with both the Second World War and Korea, conditions in Afghanistan for many of our troops were benign. Throughout the campaign they enjoyed absolute freedom of movement in the air with fast jets in ground attack mode and attack helicopters on call. Heavy artillery was usually in range – British guns fired out of Camp Bastion on our last day there. Casualty evacuation and medical support in theatre were superb, something their predecessors could only dream of.

And other than for a few senior officers, tours of duty were six months long with one rest period back in the UK. American conscripts in Vietnam served a year-long tour of duty. In Aden, the first post-National Service campaign of the British Army, the tour of duty was usually a year, with Rest & Recreation periods spent in Kenya, not back in Blighty.

Finally, although our troops experienced a distressing drip-drip of casualties, often in the most demanding circumstances, overall the individual odds - given the large number of troops who have served in Afghanistan - weren’t too bad.

We lost. And 404 British lives were lost to enemy action in the process. And each household in the United Kingdom had to contribute more than £1,000 in hard-earned income to finance this folly. I have huge sympathy for the casualties and the bereaved. We are all proud of their sacrifice. But the bottom line is that there is no point in having armed forces that keep on getting beaten – however gallant and stirring the circumstances.

It’s clear from numerous sources that the Army’s top brass were keen to redeem themselves from what they saw as a disastrous experience in Iraq with a ‘victory’ in Afghanistan. I went to one of the MoD briefings myself where a pair of gung-ho generals and a bevy of over-enthusiastic staff officers made this crystal clear.

“There are no bad soldiers in the British Army, only bad officers” is a saying drummed into cadets at Sandhurst from their first moments on the premises, usually by their grinning platoon colour sergeants – the individuals most responsible for their day-to-day training. We might refine the Army’s traditional wisdom a little further: “In Afghanistan there were no bad soldiers or officers in the British Army, just bad generals.”

They owe us an explanation in a rigorous public forum with hard-hitting terms of reference. Nothing else will do.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Aid to Ukraine: too little, too late?

Aid to Ukraine: too little, too late?Talking Point House of Representatives finally 'met the moment' but some say it came too late

By The Week UK Published

-

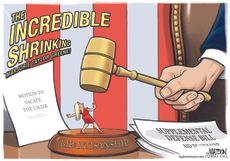

5 generously funny cartoons on the $60 billion foreign aid package

5 generously funny cartoons on the $60 billion foreign aid packageCartoons Artists take on Republican opposition, aid to Ukraine, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Knife: Salman Rushdie's 'mesmeric memoir' of brutal attack

Knife: Salman Rushdie's 'mesmeric memoir' of brutal attackThe Week Recommends The author's account of ordeal which cost him his eye is both 'scary and heartwarming'

By The Week Staff Published