Is Oscar Pistorius anxious or just angry? An analyst's view

This 'prince of the physical world' does not easily fit the description of an anxiety-ridden GAD sufferer

NEARLY at the end of his murder trial, doubt is being cast on Paralympian Oscar Pistorius’s state of mental health. A forensic psychiatrist, Dr. Meryl Vorster, has diagnosed Pistorius with Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD).

Today, under pressure from prosecutor Gerrie Nel who wants to establish the truth about Pistorius’s sanity and whether his lawyers are using GAD as a “fall-back defence”, Judge Thokozile Masipa ruled that he should be admitted to a psychiatric hospital for independent assessment. Because the testing will take 30 days, and it will need to be scheduled, this could mean a lengthy break in the court case.

Pistorius’s trial has already been going on for two months. Why is his state of mind being questioned now on the brink of a verdict? What is GAD? And does Pistorius in fact display symptoms of GAD?Vorster’s evidence was requested by Pistorius’s defence, presumably to mitigate a verdict of guilty. GAD is not classed as a mental illness in SA, but Vorster claims it would have made Pistorius paranoid about security and it would have affected his ability to judge the “wrongfulness” of shooting without seeing his target. "People with generalised anxiety probably shouldn't have firearms," she added.GAD is a relatively new diagnostic category that first appeared on the scene in 2000. As its title implies, it is a catch-all category that classifies people suffering from a range of anxieties. It is no surprise that it is the most common cause of disability in the workplace in the USA because it covers every conceivable symptom of anxiety.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The principal symptoms listed for GAD are:

- Sense of dread

- Restlessness

- Feeling constantly “on edge”

- Difficulty concentrating

- Irritability

- Muscle tension

- Sleep disturbance.

The GAD sufferer has chronic and exaggerated worry and tension that leads to lack of self-esteem, social withdrawal, and work difficulties. The GAD sufferer also typically anticipates disaster. Is this Pistorius? And, more importantly, was this Pistorius at the time of Reeva Steenkamp’s murder? Or in the past?It goes without saying that, guilty or not guilty, being accused of the murder of one’s girlfriend would make even the most innocent and level-headed defendant anxious. Perhaps especially so in the case of Pistorius whose overriding ambition to overcome his disability and his family losses has driven him relentlessly to win a seat among the gods. He has a great deal to lose. Vorster described Pistorius’s reactions in court – the recurrent retching and tears – as “genuine”. The implication is that Pistorius would not react like this if is he was guilty. But why not? There is just as much reason for him to be anxious if he is guilty – if not more. It is understandable that, whatever his feelings for his deceased girlfriend, Pistorius would find it hard to stomach this catastrophic blow to his career and reputation. He may well be retching from the realisation of his own self-destructiveness.While Pistorius would be crazy not to be showing signs of anxiety during his trial, does this mean that he suffered from anxiety on the night that Steenkamp was murdered and prior to that? Vorster points to a history of trauma and loss as Pistorius grew up, starting with the amputation of his legs when he was 11 months old, to the divorce of his parents when he was aged six, to the death of his mother from a drug reaction following surgery when he was 15. She describes his manic training sessions as a defence against overwhelming anxiety. It is true that such traumatic losses have repercussions in later life if they are not acknowledged at the time. But Pistorius does not easily fit into the description of a GAD sufferer. His determination to win and to be better than his fellow sportsmen who are abled is significant. At the age of 13 months he was fitted with prostheses and at 17 months he was walking. His mother allowed him no slack as a child, expecting him to perform equally with able-bodied children. Pistorius tells a story of his mother getting her two sons off to school, telling her older son to put his shoes on and ordering Oscar to get his legs on – “And that’s the last I want to hear of it.” Early on in his sporting career, his boxing trainer, Jannie Brooks, admits that it was six months before he realised Pistorius didn’t have legs.There may have been little comfort available for Pistorius as he was growing up, but he seems to have been given huge confidence in his abilities and his aspirations along with being unusually gifted in sports. In an extended interview with Pistorius, the New York Times journalist Michael Sokolove was struck by his “uncommon temperament – a fierce, even frenzied need to take on the world at maximum speed with minimum caution. It is an athlete’s disposition, that of a person who believes himself to be royalty of a certain kind – a prince of the physical world.” This is not the picture of an anxiety ridden man but more of a narcissistic demi-god who will take on the world to achieve his ends – and who might feel he is above the law. Gods and demi-gods don’t like to be crossed or to lose. A former girlfriend describes Pistorius, after being stopped for speeding by the police, taking the gun by his side and shooting a lamp-post. In his fiery correspondence with Steenkamp, Pistorius comes across as possessive and controlling. Steenkamp complained that Pistorius “picked” on her and told him, “I’m scared of you sometimes and how you snap at me and how you will react to me.”Despite Pistorius’s physical triumphs, the ever-present frustration of having to manage his disability would also explain his sudden unleashed anger. Whatever judgment may be made about his sanity, is this Pistorius’s real Achilles heel?

Coline Covington is a Jungian analyst in private practice in London. A collection of past columns for The Week, ‘Shrinking the News’, was recently published by Karnac Books.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Today's political cartoons - May 4, 2024

Today's political cartoons - May 4, 2024Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - reflections in the pond, riding shotgun, and more

By The Week US Published

-

5 high-caliber cartoons about Kristi Noem shooting her puppy

5 high-caliber cartoons about Kristi Noem shooting her puppyCartoons Artists take on the rainbow bridge, a farm upstate, and more

By The Week US Published

-

The Week Unwrapped: Why is the world running low on blood?

The Week Unwrapped: Why is the world running low on blood?Podcast Scientists believe universal donor blood is within reach – plus, the row over an immersive D-Day simulation, and an Ozempic faux pas

By The Week Staff Published

-

Weinstein's appeal: a blow to #MeToo

Weinstein's appeal: a blow to #MeTooTalking Point Is 'shocking' reversal of symbolic conviction a sign of weakening movement?

By The Week UK Published

-

Do youth curfews work?

Do youth curfews work?Today's big question Banning unaccompanied children from towns and cities is popular with some voters but is contentious politically

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Sydney mall attacker may have targeted women

Sydney mall attacker may have targeted womenSpeed Read Police commissioner says gender of victims is 'area of interest' to investigators

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

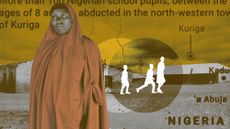

Why are kidnappings in Nigeria on the rise again?

Why are kidnappings in Nigeria on the rise again?Today's Big Question Hundreds of children and displaced people are missing as kidnap-for-ransom 'bandits' return

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

Deaths of Jesse Baird and Luke Davies hang over Sydney's Mardi Gras

Deaths of Jesse Baird and Luke Davies hang over Sydney's Mardi GrasThe Explainer Police officer, the former partner of TV presenter victim, charged with two counts of murder after turning himself in

By Austin Chen, The Week UK Published

-

How the idyllic Galapagos Islands became staging post in world drug trade

How the idyllic Galapagos Islands became staging post in world drug tradeUnder the radar Ecuador's crackdown on gang violence forces drug traffickers into Pacific routes to meet cocaine demand

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Armed gangs, prison breaks and on-air hostages: how Ecuador was plunged into crisis

Armed gangs, prison breaks and on-air hostages: how Ecuador was plunged into crisisThe Explainer Gangs launch deadly revenge after president declares state of emergency following escape of feared drug boss from prison

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Ecuador tips toward chaos amid prison breaks, armed TV takeover

Ecuador tips toward chaos amid prison breaks, armed TV takeoverSpeed Read New President Daniel Noboa authorized the military to 'neutralize' powerful drug-linked gangs after they unleashed violence and terror across Ecuador

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published