The Overton window explained

Donald Trump and Brexit are breathing new life into an old political concept

The Overton window, a political science concept born in the 1990s, has become the go-to model for commentators amid the rise of Donald Trump and Brexiteers.

The term was devised by the late free-market advocate Joseph Overton, an executive at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, a conservative think tank in Michigan. After Overton died in a plane crash in 2003, his colleague at the centre, Joseph Lehman, formalised the idea.

Now, the “once-obscure poli-sci concept is having its moment in the sun”, says Politico.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

So what is the Overton window?

The concept is used to describe the range of ideas that voters find acceptable and “outside which lie political exile or pariahdom”, explains Politico.

The theory is that politicians are limited in what policies they can support as they risk losing voters if they pursue ideas that are not seen as legitimate options by society.

The Mackinac Center explains that the Overton window “can both shift and expand, either increasing or shrinking the number of ideas politicians can support without unduly risking their electoral support”.

The think tank uses prohibition as an example of something that was deemed acceptable a few generations ago but is now outside the borders of the Overton window, meaning “virtually no politician endorses making alcohol illegal again”.

Why is it a popular term now?

The model has gained traction since Donald Trump put himself forward to become US president, although Politico notes there has been some misconception about attributing this to lawmakers themselves.

“Politicians respond to the public’s definition of the window, not the other way around,” it says.

As Lehman explains, politicians are “in the business of detecting where the window is, and then moving to be in accordance with it”.

Jackson Rawlings on Medium believes the economic crisis of 2008 led the public to “question the political status quo”, while the rise of the internet has encouraged a “herd mentality” among users who are subjected to “articles and ideas to justify basically every position possible, from Nazism to Necrophilia”.

Rawlings says people such as Trump “saw that the Window was wide open, and decided to take society through it”.

Is it a conservative phenomonen?

No. The window can expand and move in different directions.

The New York Times notes that left-wing legislation proposed by Bernie Sanders before the 2016 presidential election was deemed radical at the time.

“His support for these policies set him apart in the 2016 Democratic field, but they are mainstream positions among the 2020 candidates - because, increasingly, they are mainstream positions among the voters those candidates are courting,” says the newspaper.

In the run-up to the last presidential election, David French in the National Review claimed Trump “smashed” the window on issues such as immigration and national security.

“Registration of Muslims? On the table. Bans on Muslims entering the country? On the table. Mass deportation? On the table. Walling off our southern border at Mexico’s expense? On the table,” he wrote. But he added that “the shattering of the window reflects the shattering of the American consensus”.

What about Brexit?

Last week, Ben Kelly in The Daily Telegraph argued that the “Overton window has shifted permanently” in the UK on the subject of Brexit.

Not long ago, Brexit seemed unattainable and the majority of Eurosceptics would have “dreamt” of leaving on the terms of Theresa May’s withdrawal agreement, said Kelly. But now, for the European Research Group - the staunch Leave faction of the Tory party chaired by Jacob Rees-Mogg - “only a ‘no deal’ Brexit will do”.

In The Independent, Dan Antopolski says nudging the Overton window “should work like a courtroom: each side must present its arguments as vigorously as possible, averaging out everybody’s bias and leaving the truths exposed”.

However, he argues that the Remain campaign has failed to “show up to do their bit in the adversarial process”, leaving the window to “lurch unpredictably”.

In The Spectator last year, Alex Massie recalled how David Cameron once branded Ukip the party of “fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists, mostly”.

He concludes: “Once, the Conservatives denounced Ukip as the unacceptable face of Euroscepticism; now they dance on Ukip’s grave while carrying on with its philosophy. The Kippers have won.”

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Hollie Clemence is the UK executive editor. She joined the team in 2011 and spent six years as news editor for the site, during which time the country had three general elections, a Brexit referendum, a Covid pandemic and a new generation of British royals. Before that, she was a reporter for IHS Jane’s Police Review, and travelled the country interviewing police chiefs, politicians and rank-and-file officers, occasionally from the back of a helicopter or police van. She has a master’s in magazine journalism from City University, London, and has written for publications and websites including TheTimes.co.uk and Police Oracle.

-

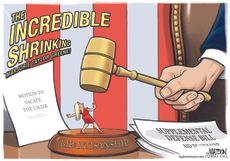

Today's political cartoons - April 27, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 27, 2024Cartoons Saturday's cartoons - natural gas, fundraising with Ted Cruz, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Aid to Ukraine: too little, too late?

Aid to Ukraine: too little, too late?Talking Point House of Representatives finally 'met the moment' but some say it came too late

By The Week UK Published

-

5 generously funny cartoons on the $60 billion foreign aid package

5 generously funny cartoons on the $60 billion foreign aid packageCartoons Artists take on Republican opposition, aid to Ukraine, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Justices set to punt on Trump immunity case

Justices set to punt on Trump immunity caseSpeed Read Conservative justices signaled support for Trump's protection from criminal charges

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

'Biden is smart to keep the border-security pressure on'

'Biden is smart to keep the border-security pressure on'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Arizona grand jury indicts 18 in Trump fake elector plot

Arizona grand jury indicts 18 in Trump fake elector plotSpeed Read The state charged Mark Meadows, Rudy Giuliani and other Trump allies in 2020 election interference case

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

'Voters know Biden and Trump all too well'

'Voters know Biden and Trump all too well'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Who will win the 2024 presidential election?

Who will win the 2024 presidential election?In Depth Election year is here. Who are pollsters and experts predicting to win the White House?

By Justin Klawans, The Week US Published

-

National Enquirer helped Trump in 2016, ex-boss says

National Enquirer helped Trump in 2016, ex-boss saysSpeed Read David Pecker says the tabloid published fabricated content to hurt Trump's rivals

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

Sitting in judgment on Trump

Sitting in judgment on TrumpOpinion Who'd want to be on this jury?

By Susan Caskie Published

-

How could the Supreme Court's Fischer v. US case impact the other Jan 6. trials including Trump's?

How could the Supreme Court's Fischer v. US case impact the other Jan 6. trials including Trump's?Today's Big Question A former Pennsylvania cop might hold the key to a major upheaval in how the courts treat the Capitol riot — and its alleged instigator

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published