Digital property: can you bequeath your iTunes library?

The laws surrounding online assets are 'very grey', but growing number of lawsuits is set to change that

WHAT do you reckon your online assets are worth? Obviously photos, videos and all those flirty exchanges charting the course of your romantic life have priceless sentimental value. But what about the doubtless burgeoning portfolio of music, films, games and e-books? Or, for that matter, your domain names, business contacts and collection of high-profile Twitter followers?

Few people make inventories of their digital property. But the matter has become increasingly pressing of late, amid a welter of court cases centring on who really owns these digital assets, and whether they can be passed on to heirs when you die. The law in Britain - as indeed elsewhere - is very grey. As is often the case with tech matters, it has struggled to keep up with the fast-moving digital industry and disputes tend to be settled on a case by case basis.

The stakes, though, are getting higher. According to figures put out by Rackspace, a web data storage company, we are currently storing nearly £30 billion worth of media online. And with digital sales rocketing by about 40 per cent in 2013, the value of that stash is set to grow much bigger.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most of the big digital providers are very clear on the subject of ownership - it doesn’t belong to you. Purchasing electronic media doesn’t give you the same rights as buying the equivalent books, DVDs and CDs - because you’re buying a lifetime licence to use these digital files rather than a hard, tangible asset.

There have been reports of people challenging these terms and conditions. In 2012, the actor Bruce Willis, was reported to be preparing to sue Apple over the right to bequeath his iTunes music collection to his daughters. It turned out to be a canard (the story was refuted by Willis’ wife Emma Heming-Willis), but it is probably only a matter of time before someone decides to have a crack at the status quo.

Indeed, according to Trevor Slack, a valuations director at accountants BDO, there may be room for Apple et al to start selling “a different class of licences which would allow for some form of limited transferability - obviously at a premium - so individuals could choose to buy a licence with more rights”.

In the meantime, there are ways round the issue. Since the Ts and Cs of some providers allow a given number of users on separate devices access to a particular account - provided they hold the same password - your heirs could still, in theory, gain access to your film library or play list after your death.

Naomi R Cahn, a professor of law at George Washington University, reckons there is also scope in trust law. “The licence may cease to exist when the account-holder dies, so it can’t be transferred in a will. But by placing the licence in a trust, it is possible it will survive the death of its creator.” Still, that does seem rather a tortuous way of ensuring that your children reap the full benefits of your heavy metal compilations.

The law is currently equally grey on the question of social media accounts.

But you can take steps to protect your legacy - and establish a degree of control over who in the family can access what after your death - by including a provision for digital assets in your will. Make sure your executors have access to a full list of passwords, as well as instructions on what you’d like distributed to whom, and what you’d like deleted. Alternatively, you can arrange this yourself via “digital life managers” like PasswordBox, whose service includes a “legacy vault” for the dispersal and/or disposal of your assets.

Of course, digital property isn’t just a legacy issue. As the Financial Times recently reported, networks of online relationships and contacts are rapidly becoming recognised as a new form of capital- with companies like Klout, Kred and PeerIndex now claiming to be able to measure the level of influence that an individual has online and condense it into a single number.

Yet the question of who exactly owns these assets promises to become a very knotty area of employment law. If, for instance, you build up a large personal Twitter following while employed by a company, does it belong to you or to them? And can you take it with you when you leave? Case law on the issue is still very patchy.

Once thing, though, is certain. It looks to be only a matter of time before would-be employers start checking out “influence scores” in much the same way as lenders access credit ratings. If you want to safeguard your future prosperity, better start building up those LinkedIn contacts.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

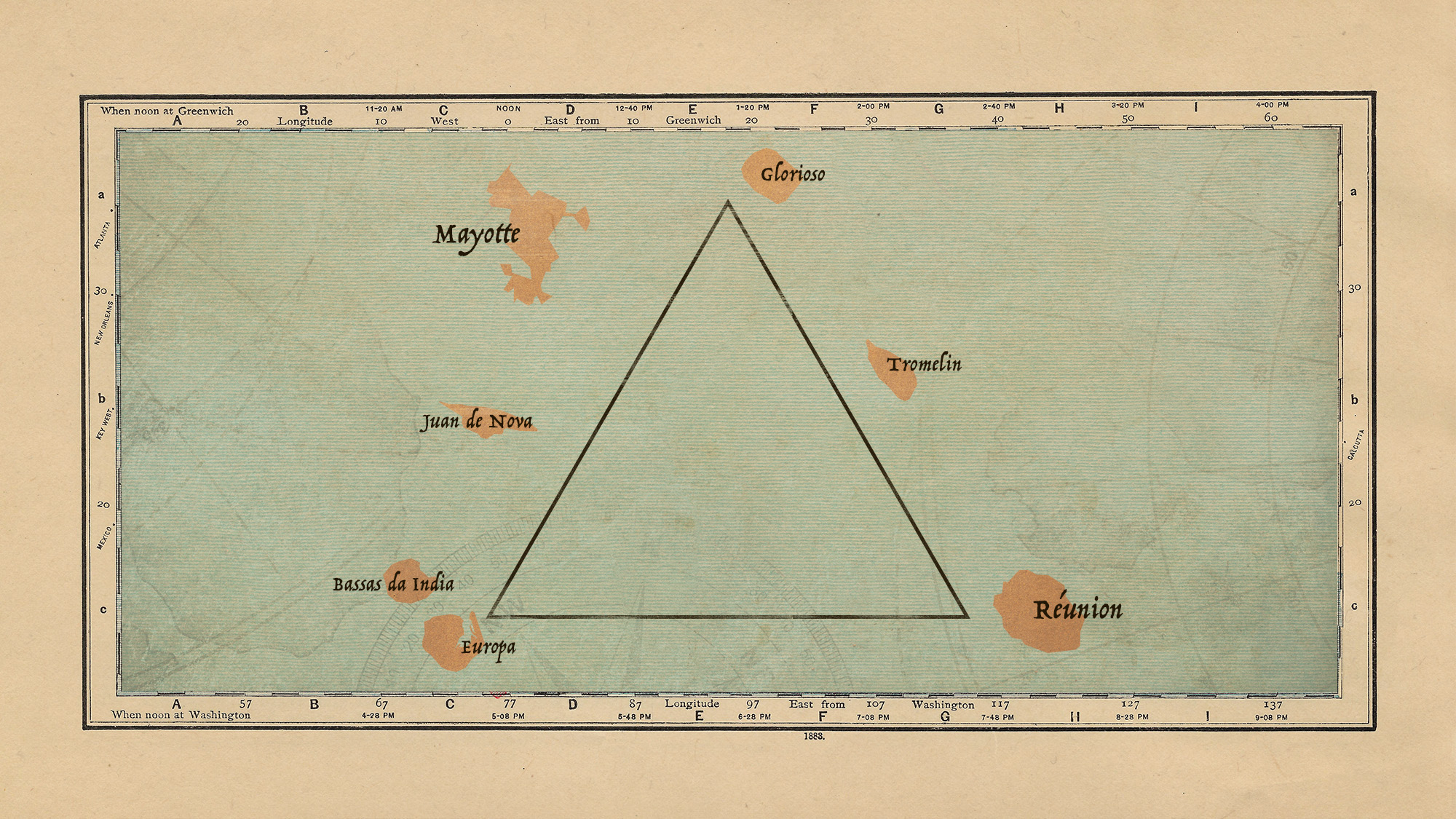

The Scattered Islands and France's 'triangle of power' in the Indian Ocean

The Scattered Islands and France's 'triangle of power' in the Indian OceanUnder The Radar Small, uninhabited but strategically important islands are a point of contention between France and Madagascar

-

6 isolated homes for hermits

6 isolated homes for hermitsFeature Featuring a secluded ranch on 560 acres in New Mexico and a home inspired by a 400-year-old Italian farmhouse in Colorado

-

Magazine solutions - May 9, 2025

Magazine solutions - May 9, 2025Puzzles and Quizzes Issue - May 9, 2025

-

China clears path to new digital currency

China clears path to new digital currencySpeed Read Unlike other cryptocurrencies, Beijing’s would increase central control of the financial system

-

Facebook blocks Admiral's profile-trawling plan

Facebook blocks Admiral's profile-trawling planSpeed Read Car insurer had planned to use users' timeline posts to offer young drivers discounts on premiums

-

Technology shares in decline: Dotbomb 2.0 or slow puncture?

Technology shares in decline: Dotbomb 2.0 or slow puncture?In Depth Shares in tech giants including Google, Yahoo and Facebook fall sharply, but could it be time to invest?