What was Watergate and why was it so important?

The story behind the infamous break-in which brought down a president – and why it still has an impact today

The release of an explosive new book by one of the journalists at the heart of the Watergate scandal has prompted comparisons between the Nixon and Trump administrations.

Fear: Trump in the White House, by Bob Woodward, goes on sale today, 46 years after a break-in at the Democratic Party HQ in the Watergate building triggered an investigation that uncovered illegal activities, cover-ups and conspiracies right in the heart of the White House.

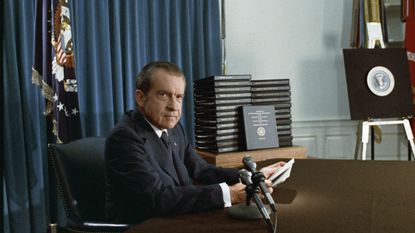

Watergate, as it became known, eventually brought down president Richard Nixon, forcing him to resign, after it was revealed he had lied to the US public about his involvement in the burglary.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The impact of the crisis was so powerful that scandals around the world are still dubbed “gates”. But what actually happened, why was it so important - and can parallels really be drawn with the present day.

The cover-up

Police were called out to Watergate in the early hours of 17 June 1972 and arrested five men - Virgilio Gonzalez, Bernard Barker, James McCord, Eugenio Martinez and Frank Sturgis – who were attempting to break into the complex, carrying photographic equipment and bugging devices.

The subsequent FBI investigation uncovered address books belonging to two of the burglars linking them to former CIA agent E Howard Hunt, who had become a leading member of the Committee to Re-elect the President (officially the CRP, but commonly referred to as Creep), which was working to see Nixon back in the White House for a second term.

Creep’s activities ranged from the unethical to the illegal, including wiretapping, money-laundering, harassment of activist groups and even, says Irish news site The Journal, stealing the shoes of Democratic campaign workers.

It would later be discovered that Hunt and a fellow committee member, G Gordon Liddy, were in the hotel opposite Watergate during the break-in, guiding the burglars via walkie-talkie.

Despite the link to his campaign, Nixon categorically denied any White House involvement - but in private, the administration leaned on the CIA to put a stop to the FBI inquiry.

Woodward and Bernstein

Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward were instrumental in providing the evidence that directly linked the burglary to the Nixon administration.

Crucial to their investigation was a source known only as “Deep Throat”, an anonymous FBI official finally identified in 2005 as the bureau’s deputy director, Mark Felt. He supplied the two journalists with vital leads and a simple but ultimately revelatory tip: “Follow the money.”

Doing so, Bernstein discovered one of the burglars had received a cheque for $25,000 from Creep, taken from campaign contributions.

The story was ignored by the most of the media and Nixon was easily re-elected in November 1972, but Woodward and Bernstein continued to pursue the connection between Watergate and the White House.

The book they would later write about it, All the President’s Men, was turned into a hit film starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in 1976.

Things fall apart

Six months after the break-in, burglar McCord, along with Liddy, was found guilty of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. Five other men, including Hunt, had already pleaded guilty.

But it was two months after that, in March 1973, when the Watergate affair truly came back with a bang. McCord, a former CIA agent, accused senior White House officials of pressuring him to give false testimony in order to disguise the administration’s involvement in illegal activities.

A few days later, fearing he was going to be used as a scapegoat in the scandal, Nixon’s legal counsel John Dean agreed to cooperate with investigators.

Two of the president’s closest aides, HR Haldeman and John Ehrlichman, along with attorney general Richard Kleindienst, resigned the following month.

Nixon was forced to accept responsibility for Watergate for the first time, although he continued to deny personal involvement. That was about to change.

The tapes

In May 1973, the United States was gripped as the Senate select committee on presidential activities began televised hearings into the case.

Witness testimony unravelled the connection between the White House and Creep’s dirty dealings, including Watergate.

But the most explosive revelation came from former White House official Alexander Butterfield, who revealed that all the conversations and phone calls in the Oval Office had been recorded since 1971.

A subpoena was immediately sent out to access the recordings. Nixon, however, refused, invoking presidential privilege.

“I am not a crook,” he told the US public in November of that year, as the legal wrangling continued.

It took a Supreme Court ruling in July 1974 to force him to hand over the tapes. The contents were damning. Recorded conversations “showed that Nixon had, contrary to repeated claims of innocence, played a leading role in the cover-up from the very start”, says the Washington Post.

Facing impeachment, Nixon resigned on 8 August 1974.

Forty-eight government officials were convicted of participating in the cover-up. The scandal was over, but its impact would continue to reverberate for years to come.

The aftermath

Watergate “was the worst scandal in American history for it was an attempt to subvert the American political process itself”, says PBS. Campaign finance reforms were enacted to minimalise the risk of any future legal misconduct, but the real damage was on a cultural level.

The US public were now “divided between disillusioned, defeated and bitter conservatives and mistrustful, alienated and confrontational liberals”, writes author Andrew Downer Crain.

However, the lasting legacy of Watergate has been the political polarisation of the US. Republicans and Democrats began to drift apart sharply in the wake of the scandal - and the rift only continues to grow with time.

Are there any parallels with modern politics?

“What would Watergate look like if it were to happen now?” The New York Times asks, before answering its own question: it looks like Donald Trump.

For months, “the Trump administration and its scandals have carried whiffs of Watergate and drawn comparisons to the characters and crimes of the Nixon era”, says CBS News.

In fact “nearly every element in Trump's trouble has a Watergate parallel”, the news organisation adds.

“This is a president who says things publicly that we know from the tapes that Nixon said privately,” Timothy Naftali, a New York University historian who directed the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, tells CBS. “It's as if Trump is wrestling with the history of Watergate openly. It's the president who is inviting these parallels.”

Special prosecutor Robert Mueller is leading an independent investigation sparked by a break-in at the Democratic National Committee, though this time the burglary was digital and linked to Moscow, not the Oval Office.

Tales from inside Trump’s White House have recently arrived in the form of an anonymous New York Times op-ed penned by a senior administration official, as well as the 448-page book by Woodward. These reports describe an administration in disorder, complete with an aloof president in Trump who appears incapable of leading the nation.

Andrew Hall, who was present when four of Nixon’s top advisers were sentenced to prison for their roles in Watergate, believes he is watching history repeat itself.

“The coverup is always worse than the crime,” Hall tells The Independent. “And this one is very shady. We have a sitting president who will undoubtedly be impeached.”

But so far Trump is not accused of any crime and the series of convictions against Trump campaign aides has not unearthed collusion between Russia and the campaign.

Therefore the parallels with Watergate only go so far, says Naftali.

Yet “Nixon's playbook for dirty tricks and abuse of power and political espionage is a useful source of questions for any investigation of an impulsive, erratic and potentially criminal presidency,” he adds. “We'll be watching. The Nixon presidency makes us smarter as we try to make sure that our presidents don't do what Nixon did.”

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

'Most see a guilty verdict for Trump'

'Most see a guilty verdict for Trump'Today's Newspapers A roundup of the headlines from the US front pages

By The Week Staff Published

-

British Armed Forces personnel details 'hacked by China'

British Armed Forces personnel details 'hacked by China'Speed Read The Ministry of Defence became aware of the breach 'several days ago'

By Arion McNicoll, The Week UK Published

-

Best beach cafes around the UK

Best beach cafes around the UKThe Week Recommends Enjoy freshly cooked food within sight of the sea – whatever the weather

By Adrienne Wyper, The Week UK Published

-

The Don's enablers

The Don's enablersOpinion Even Republicans who know better won't get in Trump's way

By William Falk Published

-

'Climate studies are increasingly becoming politicized'

'Climate studies are increasingly becoming politicized'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

What would it be like in jail for Trump if he's convicted?

What would it be like in jail for Trump if he's convicted?Today's Big Question The Secret Service has begun grappling with how to protect a former president behind bars

By Rafi Schwartz, The Week US Published

-

'A financial windfall for Iranian terrorism'

'A financial windfall for Iranian terrorism'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

'Box Trump in for real if he pulls another stunt. Put him behind bars.'

'Box Trump in for real if he pulls another stunt. Put him behind bars.'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

'Can we — the people who have bought so much already — really keep buying more?'

'Can we — the people who have bought so much already — really keep buying more?'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

'Presidential debates are more performance art than actual ways to inform'

'Presidential debates are more performance art than actual ways to inform'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Trump, DeSantis meet for first time since primary

Trump, DeSantis meet for first time since primarySpeed Read The former president and the Florida governor have seemingly mended their rivalry

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published