Is modern life raising our blood pressure?

Study of remote communities in Venezuelan rainforest sheds fresh light on hypertension

The common consensus that higher blood pressure is an inevitable consequence of aging has been upended by a newly published study about two isolated Amazon tribes.

According to the researchers, hypertension may actually be a result of certain aspects of Western lifestyles, “such as high levels of salt in the diet, lack of exercise and heavy drinking”, The Guardian reports. As the newspaper notes, high blood pressure is a key risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

The new research focused on two remote tribes living around the border of Brazil and Venezuela: the Yanomami and the Yekwana.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Yanomami tribe “has proved particularly compelling to scientific researchers as several decades of study has revealed they have significantly low blood pressure levels, which do not seem to rise as they age”, says wildlife magazine New Atlas. The nearby Yekwana people are also fairly isolated but get regular deliveries of Western food and medicine via a local airstrip.

The study, published in the journal Jama Cardiology, looked at 72 Yanomami and 83 Yekwana people aged between one and 60.

Although ”the two groups were similar in other respects, average blood pressure among the Yanomami was 95/63, whereas in the Yekwana it was 104/66”, reports The Washington Post.

By the age of 60, blood pressure among the Yanomami remained unchanged, while the Yekwana average had risen to 114/73.

Study author, Noel T. Mueller, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Baltimore-based university Johns Hopkins, told the Post that this difference in blood pressure levels was found even in children. By the age of ten, Yekwana children had significantly higher blood pressure, with the divergence increasing with age.

“[That] to us indicates that interventions to prevent the rise in blood pressure and high blood pressure need to start early in life, where we can still have the opportunity to modify some of the exposures that might lead to high blood pressure,” Mueller said.

He added that while it may not be feasible to follow a Yanomami diet, just cutting salt intake in half could prevent an estimated 15 million cases of hypertension in the US alone.

“That blood pressure rises over age is probably not a natural phenomenon, but a cumulative effect of exposure to the Western diet,” he said. “Following a healthful diet low in processed food and salt can help reduce the risk for hypertension.”

However, some scientists have cast doubt over the findings, pointing to the small scale of the study and the lack of information about the tribes’ genetic make-up.

“It is unclear whether these factors fully explain the results, which may also be partly due to genetic factors,” said Dr James Sheppard, an expert in hypertension at Oxford University who was not involved in the study.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Today's political cartoons - April 14, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 14, 2024Cartoons Sunday's cartoons - Trump Derangement Syndrome, social media dangers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

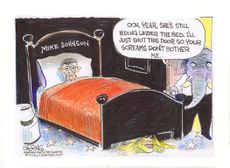

5 rambunctious cartoons about the House speakership standoff

5 rambunctious cartoons about the House speakership standoffCartoons Artists take on Mike Johnson's night terrors, the Speaker's chair, and more

By The Week US Published

-

The Week Unwrapped: Ultrarunning, menswear and a meaty row

The Week Unwrapped: Ultrarunning, menswear and a meaty rowPodcast Is the "Hardest Geezer" a high-endurance trendsetter? Will Ted Baker survive? And what's the beef with lab-grown meat?

By The Week Staff Published

-

Inside Venezuela’s oil corruption scandal

Inside Venezuela’s oil corruption scandalfeature Private planes and luxury cars seized as £17bn allegedly goes missing from state-run company

By Harriet Marsden Published

-

French cheesemakers livid over poll

French cheesemakers livid over pollfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden Published

-

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drug

Home Office worker accused of spiking mistress’s drink with abortion drugSpeed Read Darren Burke had failed to convince his girlfriend to terminate pregnancy

By The Week Staff Published

-

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policy

In hock to Moscow: exploring Germany’s woeful energy policySpeed Read Don’t expect Berlin to wean itself off Russian gas any time soon

By The Week Staff Published

-

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?

Were Covid restrictions dropped too soon?Speed Read ‘Living with Covid’ is already proving problematic – just look at the travel chaos this week

By The Week Staff Last updated

-

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UK

Inclusive Britain: a new strategy for tackling racism in the UKSpeed Read Government has revealed action plan setting out 74 steps that ministers will take

By The Week Staff Published

-

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakers

Sandy Hook families vs. Remington: a small victory over the gunmakersSpeed Read Last week the families settled a lawsuit for $73m against the manufacturer

By The Week Staff Published

-

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’

Farmers vs. walkers: the battle over ‘Britain’s green and pleasant land’Speed Read Updated Countryside Code tells farmers: ‘be nice, say hello, share the space’

By The Week Staff Published