Poussin and the Dance: a small but revelatory exhibition, packed with ‘fabulous moments’

Poussin’s reputation as an ‘austere landscapist’ is only half the story, proves this National Gallery show

Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665) is “a problematic presence in art”, said Waldemar Januszczak in The Sunday Times. “Nothing about him quite fits”: although he was French, he spent most of his career in Rome, and while his dates are roughly equivalent to Rembrandt’s, you might assume they had lived in different centuries altogether.

Poussin was a stickler for precision, taking a formal and academic approach that makes much of his work “cool and erudite to the point of being off-putting”. Yet as this new exhibition at the National Gallery shows, Poussin’s reputation as an “austere landscapist” is only half the story.

Concentrating on the early phases of his career, the show presents the artist as “a lover of the classical world at its naughtiest”, a painter of “gorgeous” sunlit scenes, “beautiful nymphs” dancing in forest glades, and bacchanalian scenes of love and intoxication. Bringing together a small but revelatory selection of glorious paintings, “dazzling” drawings and a variety of exhibits explaining his working methods, it is packed with “fabulous moments”.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

If the show makes one thing clear, it’s that Poussin was a “colossal nerd”, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. When he arrived in Rome in 1624, he carried around a tape measure to record precise dimensions of the city’s classical statues. More “obsessive” still, he based the figures in his paintings on “laboriously constructed” wax figurines he built in his studio, a few replicas of which we see here.

Sometimes, these “strange” working methods paid off: the drawings featured are “remarkably vigorous”. The paintings, however, feel “measured, detached, even artificial”: they may depict Dionysian scenes, but Poussin has no interest in “conveying the sensation of being amid the mêlée”, instead giving us technically perfect exercises in “studied elegance”. There is “too much decorum, not enough rapture or raunch”.

It’s true that Poussin was never a particularly “fun” artist, said Laura Cumming in The Observer. Even so, it’s remarkable to see these scenes of “wild abandon”, painted with such “precise conceptual engineering” – the figures at once “technically in motion” and “spellbindingly still”. Nowhere is this clearer than in the last picture here, the “masterpiece” A Dance to the Music of Time. Four female figures dance “a merry-go-round beginning to slow out of kilter”, their motion “not so much graceful as disturbing”; one of the dancers is visibly “flagging”, her hand slipping from her partner’s. Time itself is represented by a winged harpist, “his expression sardonic as he watches the dance that must soon come to an end”. It is the highlight of a gripping and “beautifully choreographed” exhibition.

The National Gallery, London WC2 (020-7747 2885, nationalgallery.org.uk). Until 2 January 2022

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

'Republicans want to silence Israel's opponents'

'Republicans want to silence Israel's opponents'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Poland, Germany nab alleged anti-Ukraine spies

Poland, Germany nab alleged anti-Ukraine spiesSpeed Read A man was arrested over a supposed Russian plot to kill Ukrainian President Zelenskyy

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

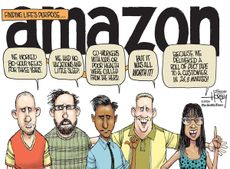

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 19, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - priority delivery, USPS on fire, and more

By The Week US Published

-

6 serene homes in Vermont

6 serene homes in VermontFeatures Featuring a four-level Shaker barn in Hartland and a Scandinavian-inspired home in Stowe

By The Week US Published

-

Amanda Montell's 6 favorite books that will expand your knowledge

Amanda Montell's 6 favorite books that will expand your knowledgeFeature The linguist recommends works by Mary Roach, Alice Carrière, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Rowan Beaird recommends 6 compelling books from the 1950s

Rowan Beaird recommends 6 compelling books from the 1950sFeature The author recommends works by Patricia Highsmith, Shirley Jackson, and more

By The Week US Published

-

6 spacious homes with great rec rooms

6 spacious homes with great rec roomsFeature Featuring a suspended fireplace in Arizona and a marine-themed home in Maine

By The Week Published

-

Recipe: gnocchi di spinaci (spinach gnocchi)

Recipe: gnocchi di spinaci (spinach gnocchi)The Week Recommends Forget the potatoes for this gnocchi made of the 'classic combination' of spinach and ricotta

By The Week UK Published

-

Stephen Graham Jones' 6 scary books with deeper meanings

Stephen Graham Jones' 6 scary books with deeper meaningsFeature The best-selling author recommends works by Stephen King, Sara Gran, and more

By The Week US Published

-

6 stylish homes on the top floor

6 stylish homes on the top floorFeature Featuring a 1925 art deco high-rise in San Francisco and a factory-turned-home in Los Angeles

By The Week US Published

-

The Anxious Generation: US psychologist Jonathan Haidt's 'urgent and essential' new book

The Anxious Generation: US psychologist Jonathan Haidt's 'urgent and essential' new bookThe Week Recommends Haidt calls out 'the Great Rewiring of Childhood' phenomenon

By The Week UK Published