Understanding Hamas: part terrorism, part good works

Three things you should know before writing off Hamas as just a violent terrorist organisation

Hamas is an internationally-designated terrorist organisation. Its attacks have killed more than 400 Israelis since 1993. It has claimed responsibility for more than 50 suicide attacks and has fired more than 2,000 rockets at civilian areas in Israel during this month's Operation Protective Edge alone.

The fact that these rockets have killed only two civilians so far during the current conflict does not excuse Hamas of the war crime of indiscriminately attacking non-combatants, something noted by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights this week.

Hamas has further been accused of numerous human rights violations within Gaza, including arbitrary detention, extra-judicial killings and torture. In short, these are not the good guys - and this is not an attempt to defend any of their crimes.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But the terrorist label prevents any sort of nuanced or deeper understanding of this group; it obscures the reasons why, aside from its violent stance, Hamas has become a key player in the Israel-Palestine conflict.

For as well as being a terrorist organisation, it is a democratically elected party, a grassroots social welfare movement, and an imperfect alternative to years of governmental corruption and lack of progress toward a Palestinian state.

Without seeking to justify any of the group's actions, here are three things you should know about Hamas and its growth in influence:

1. Much of its popularity has nothing to do with its radicalism.

The founder of Hamas - an acronym for the Arabic for Islamic Resistance Movement that also means 'zeal' - was Sheikh Ahmed Yassin. The Council on Foreign Relations describes him as a Palestinian spiritual leader and Muslim Brotherhood activist who started off preaching and performing charitable work in the Gaza Strip and West Bank during the 1960s.

Just as Muslim Brotherhood groups did in other countries across the Middle East, most notably Egypt, Hamas won grassroots support through its welfare work with impoverished, neglected people rather than through its violent methods, although undoubtedly it attracted followers because of this too.

"Despite its militant reputation," the Council on Foreign Relations adds, "Hamas's local support in many ways can be traced to its extensive network of on-the-ground social programming, including food banks, schools, and medical clinics ... Hamas devotes much of its estimated $70 million annual budget to an extensive social services network."

The group's rise to prominence and continued success is further bolstered by disillusionment with Fatah, the other main Palestinian party, widely seen as corrupt and incompetent, especially following the failure of the 1994 Oslo Accords to secure an independent Palestinian state.

2. The 2006 election was not a unanimous vote for terrorism.

In January 2006, Hamas became the first Islamist group in the Arab world to gain power democratically. Under the name Change and Reform, it won 74 out of 132 seats in an election that was deemed by the EU election observation mission to have "impressive voter participation in an open and fairly-contested electoral process".

The fundamentalist group achieved way more than anyone had predicted, but this does not mean it should be seen as a unanimous vote by Palestinians in support of Hamas's more radical stances.

Hamas won 44.45 per cent of the list seats, giving it just one more seat than Fatah. It was the constituency voting that gave it the edge on its rival, snatching up just over two-thirds of the available seats with only 40 per cent of the votes.

Exit polls showed that only a minority of people - just nine per cent - were voting based on parties' plans, whether violent or peaceful, to solve the Palestinian–Israeli conflict.

"The two most important issues for the voters were corruption in the Palestinian Authority - which is dominated by Fatah - and the inability of the PA to enforce law and order... Almost two-thirds had rated these two issues as their highest priorities," Khalil Shikaki, a prominent pollster and director of the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, wrote in Newsweek at the time.

3. The thrust of its oft-cited Charter is now irrelevant.

Yes, Hamas's 1988 founding Charter does pledge to "raise the banner of Allah over every inch of Palestine" (a reference to historic Palestine which includes modern-day Israel, the West Bank and Gaza).

Yes, it does state that "jihad is its path and death for the sake of Allah is the loftiest of its wishes."

Yes, it does say that it believes "the land of Palestine is Islamic Waqf [endowed property] consecrated for future Muslim generations until Judgement Day" - eerily similar to the claim by extremist Israelis that the West Bank, what they call Judea and Samaria, was gifted to them by God.

Yes, it does reject previous peace agreements made by the Palestinian Liberation Organisation. And yes, it does compare Israel to the Nazis on numerous occasions and conflates Jews and Israelis at will.

So there is no denying that this is the founding document of a fundamentalist Islamist organisation born at the start of the First Palestinian Intifada (uprising) with violent intentions and a clearly anti-Semitic bent.

But while Hamas has largely stayed true to this general description, some believe its Charter is no longer representative of its aims and is more of an historical relic.

Most importantly, Hamas dropped its call for the destruction of Israel in its election manifesto in 2006. Three years later, leader Khaled Meshaal said unequivocally that he would accept a Palestinian state within the pre-1967 borders, the basis for all peace negotiations, a statement that implicitly recognises Israel's right to exist.

Hamas continues to refuse to recognise Israel right to exist as a Jewish state because this would undermine the near-universal Palestinian demand for the UN-mandated right of displaced refugees to return to their original homes in Israel, something Fatah clings to as well.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Venetia Rainey is a Middle East correspondent for TheWeek.co.uk based in Lebanon where she works for the national English-language paper, The Daily Star. Follow her on Twitter @venetiarainey.

-

'Making a police state out of the liberal university'

'Making a police state out of the liberal university'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

8 looming climate tipping points that imperil our planet

8 looming climate tipping points that imperil our planetThe Explainer New reports detail the thresholds we may be close to crossing

By Devika Rao, The Week US Published

-

Try 6 free issues of The Week Junior

Try 6 free issues of The Week JuniorSpark your child's curiosity with The Week Junior - the award-winning current affairs magazine for 8-14s.

By The Week Published

-

Do youth curfews work?

Do youth curfews work?Today's big question Banning unaccompanied children from towns and cities is popular with some voters but is contentious politically

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Scotland Yard, Gaza and the politics of policing protests

Scotland Yard, Gaza and the politics of policing protestsTalking Point Met Police accused of 'two-tier policing' by former home secretary as new footage emerges of latest flashpoint

By The Week UK Published

-

Sydney mall attacker may have targeted women

Sydney mall attacker may have targeted womenSpeed Read Police commissioner says gender of victims is 'area of interest' to investigators

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

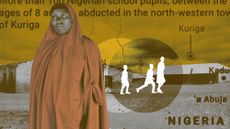

Why are kidnappings in Nigeria on the rise again?

Why are kidnappings in Nigeria on the rise again?Today's Big Question Hundreds of children and displaced people are missing as kidnap-for-ransom 'bandits' return

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

The #MeToo movements around the world

The #MeToo movements around the worldThe Explainer French men have been sharing stories of abuse in the latest calling out of sexual assault and harassment

By The Week Staff Published

-

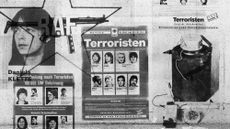

The Red Army Faction: German fugitive arrested after decades on run

The Red Army Faction: German fugitive arrested after decades on runWhy Everyone's Talking About Police reward and TV appeal leads to capture of Daniela Klette, now 65

By The Week UK Published

-

Deaths of Jesse Baird and Luke Davies hang over Sydney's Mardi Gras

Deaths of Jesse Baird and Luke Davies hang over Sydney's Mardi GrasThe Explainer Police officer, the former partner of TV presenter victim, charged with two counts of murder after turning himself in

By Austin Chen, The Week UK Published

-

How the idyllic Galapagos Islands became staging post in world drug trade

How the idyllic Galapagos Islands became staging post in world drug tradeUnder the radar Ecuador's crackdown on gang violence forces drug traffickers into Pacific routes to meet cocaine demand

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published