Nato vs. Russia: who would win?

Moscow's military expansion and threats to Baltic states increase risk of direct conflict with Western alliance

Since Vladimir Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Nato has scrambled to present a united front against Russian aggression.

Its member states have plied Kyiv with weapons and punished Russia with the most severe economic sanctions ever imposed on a major economy. But they have wavered on Ukraine's bid to join the alliance and remain divided over further financial and military support for the battered country.

The Nato-Ukraine Council met in Brussels on Wednesday as "unprecedented air attacks from Russia" were hitting Ukraine, said Politico. Ukrainian foreign minister Dmytro Kuleba hoped to secure commitments to help his country's defences. The military alliance guaranteed its ongoing military support for Ukraine at its summit last year, but stopped short of offering a clear timeframe on its accession.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The latest

Putin wants “to prepare Russia for a potential future large-scale conventional war” with Nato, a major think tank warned in December, after moving troops towards Russia's northwest where it shares borders with Finland, Latvia and Estonia.

Its restructuring of its military and expansion into the northwest, and remarks from Putin himself, were indicative of the Kremlin's "hostile intent" towards the alliance, said the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), and posed a "credible – and costly – threat to Western security".

Putin has issued "a veiled threat" to Finland, said The Independent's Asia reporter Arpan Rai, with the formation of a new military zone known as the Leningrad Military District (LMD) in the wake of Finland's decision to join Nato in April. Finland had said it had "no choice but to end decades of neutrality" in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Sweden, which is still "sat in the Nato waiting room" until Hungary and Turkey drop their opposition to its accession, has committed to sending "ground combat units" to Nato operations along the Russian border, said Newsweek's diplomatic correspondent David Brennan.

Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson said this week that Stockholm would not wait for ratification of its membership bid to send troops to Latvia on Nato's eastern frontier. "Sweden and its neighbours are living in the direct shadow of Russia's war of aggression," he said.

US President Joe Biden warned in December that Russia would attack a Nato country even if it defeated Ukraine, potentially triggering World War Three. Pleading with Republicans in Congress not to block emergency funding for Ukraine, Biden said that Putin would "not stop there", and that it would result in American troops fighting Russia.

Putin dismissed the remarks "as complete nonsense", reported Reuters. The president told Rossiya state television that Russia had "no reason, no interest – no geopolitical interest, neither economic, political nor military – to fight with Nato countries".

But since New Year's Eve the Kremlin has intensified its bombardment of Ukraine, launching one of the most brutal attacks since the war began. Nato forces were scrambled more than 300 times in response to encroachment by Russian military aircraft into its airspace over the Baltic Sea, the alliance said in a statement.

Nato’s capability

A mutual assistance clause sits at the heart of the security alliance, which was formed in 1949 with the aim of countering the risk of a Soviet attack on allied territory. Article 5 of Nato's Washington Treaty says that an attack on one ally is considered an attack on all member states – which presents an obstacle for Ukraine's membership while it remains at war with Russia.

A Nato pledge asks members to spend 2% of gross domestic product on defence. Though less than a third of members meet this target, Nato Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg has said it is "increasingly considered a floor, not a ceiling".

Nato's biggest player, the US, spends more on defence than the next 10 spenders in the world combined. Its total in 2022 was about $877 billion, according to Trading Economics – nearly 40% of the total military spending worldwide that year. The UK sits in sixth place, with spending of £68.5 billion.

The US boasts a powerful arsenal and a huge amount of manpower. According to World Population Review figures, it has 1.39 million active troops, beaten only by India and China. As of last March, Nato had about 5.8 million active military personnel, Statista data indicated.

A coalition of Nato countries has purchased 1,000 Patriot missiles to replenish "dwindling Western stockpiles", The Daily Telegraph reported this week. Stoltenberg hailed the “timely announcement" that would "bolster the alliance’s security".

Russia’s capability

Despite Russian forces' well-publicised struggles, their overall military capability is considerable. The country went from the fifth largest defence spender in the world in 2021 to the third in 2022 (behind the US and China), with a jump of more than £20 billion.

It has 1.33 million active military personnel, according to Statista, but only about 4,182 military aircraft compared with Nato's combined 20,633, and 598 military ships compared to Nato's 2,151.

"Russia's ground combat vehicle capacity is more competitive," said Statista. However, "the combined nuclear arsenal of the United States, United Kingdom, and France amounted to 5,943 nuclear warheads, compared with Russia's 5,977."

Many experts believe the country's military effectiveness was dented by the disbanding of the Wagner Group after its abortive mutiny last year. It could take Russia "up to 10 years to restore its military capabilities to their former strength", the UK Ministry of Defence intelligence update reported in December. A "staggering increase" of average daily casualties is "indicative of weakened Russian military forces", said Business Insider, and a transition towards a "lower-quality, high-quantity mass army".

Russia's "blundering army" could not beat Ukraine's 2nd XI, said The Guardian's foreign affairs commentator, Simon Tisdall, last summer – "even when sober and with the wind behind it".

Nato vs. Russia

For Putin, a Russia-Nato conflict would be "political and military suicide", said Tisdall. But Russian journalist and military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer told DW that open warfare often comes down to far more than the inventories that each side can call upon.

"It's like predicting the result of a soccer match: yes, basically, Brazil should beat America in soccer, but I have seen Americans beat Brazil in South Africa," said Felgenhauer. "You never know the result until the game is played."

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Harriet Marsden is a writer for The Week, mostly covering UK and global news and politics. Before joining the site, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, specialising in social affairs, gender equality and culture. She worked for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent, and regularly contributed articles to The Sunday Times, The Telegraph, The New Statesman, Tortoise Media and Metro, as well as appearing on BBC Radio London, Times Radio and “Woman’s Hour”. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, London, and was awarded the "journalist-at-large" fellowship by the Local Trust charity in 2021.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

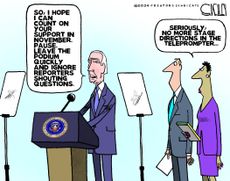

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published

-

How would we know if World War Three had started?

How would we know if World War Three had started?Today's Big Question With conflicts in Ukraine, Middle East, Africa and Asia-Pacific, the 'spark' that could ignite all-out war 'already exists'

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Will Iran attack hinder support for Ukraine?

Will Iran attack hinder support for Ukraine?Today's Big Question Pro-Kyiv allies cry 'hypocrisy' and 'double standards' even as the US readies new support package

By Elliott Goat, The Week UK Published

-

The issue of women and conscription

The issue of women and conscriptionUnder the radar Ukraine military adviser hints at widening draft to women, as other countries weigh defence options amid global insecurity

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Why is Ukraine backing far-right militias in Russia?

Why is Ukraine backing far-right militias in Russia?Today's Big Question The role of the fighters is a 'double-edged sword' for Kyiv, say commentators

By The Week UK Published

-

Why is Islamic State targeting Russia?

Why is Islamic State targeting Russia?Today's Big Question Islamist terror group's attack on 'soft target' in Moscow was driven in part by 'opportunity and personnel'

By Elliott Goat, The Week UK Published

-

Ukraine's unconventional approach to reconstruction

Ukraine's unconventional approach to reconstructionUnder the radar Digitally savvy nation uses popular app to file compensation claims, access funds and rebuild destroyed homes

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

What does victory now look like for Ukraine?

What does victory now look like for Ukraine?Today's Big Question Not losing is as important as winning as the tide turns in Russia's favour again

By Elliott Goat, The Week UK Published

-

Where has the Wagner Group gone?

Where has the Wagner Group gone?Today's Big Question Kremlin takes control of Russian mercenaries after aborted mutiny and death of leadership

By Elliott Goat, The Week UK Published