How the 2011 London riots unfolded

A decade has passed since the capital experienced the biggest riots in modern English history

Ten years ago this week, riots spread across London and other major English cities, sparked by the death of 29-year-old Mark Duggan, who was shot dead by police in Tottenham on 4 August 2011.

The riots – the biggest in modern English history – lasted for five days and swept the capital, from Wood Green to Woolwich. By 9 August, the unrest had developed nationally, reaching other cities including Birmingham, Manchester and Wolverhampton.

By the time the unrest subsided on 12 August, the capital had increased the number of police officers on the street from 3,000 to 16,000. During the period of violence, more than 3,000 arrests were made and five people died.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But how did the riots unfold and what is the legacy of this watershed moment in British culture a decade on?

The shooting of Mark Duggan

On Thursday 4 August, Duggan, a father of four, was shot dead by Metropolitan Police officers as he got out of a taxi in Tottenham, north London. His death happened during an intervention with officers from Operation Trident, a unit targeting gun crime in London, who were attempting to carry out an arrest, reported the BBC in 2015.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), now called the Independent Office for Police Conduct, later admitted to wrongly giving journalists the impression that shots had been fired by Duggan.

At first, the shooting drew “little attention”, writes former Downing Street official Craig Oliver in a retrospective of the ensuing events in The Times. “But it turns out there was no gun (though one was found near by)” and Duggan’s relatives and friends were “distraught and incensed”.

David Lammy, the Labour MP for Tottenham, said he was “shocked and deeply worried” about the incident, and on Saturday 6 August 300 people gathered outside Tottenham police station to protest the shooting, saying they wanted “justice” for Duggan and his family.

Part of the reason for their demonstration was down to the “alleged failure by the IPCC to provide Duggan’s family and the local community with reliable information in the aftermath of his death”, wrote The Guardian at the time.

The newspaper says “two different portraits were painted” of Duggan that week, a “hardened north London gangster and drug dealer” and a “loving family man who would never seek confrontation”.

A 2014 inquest found the shooting to be lawful but concluded that Duggan did not have a weapon in his hands when confronted by police and had thrown it from the taxi.

Peaceful protests turn violent

According to the BBC, the protests started peacefully, with the demonstration outside Tottenham police station on 6 August, but a “confrontation between a teenage protester and a police officer” sparked violence, with bottles being thrown at two patrol cars, which were then set alight. Riot officers and police on horseback were “deployed to disperse the crowds”, but “came under attack from bottles, fireworks and other missiles”.

The peaceful gathering “culminated 12 hours later in a full-scale riot that saw brazen looting spread across north-London suburbs”, reported The Guardian at the time. The protest had been “good-natured”, added the paper, but what became clear over the next four hours was that as tensions “gradually escalated”, the “police made only limited attempts to talk to the demonstrators”.

By 11pm that evening, a double-decker bus had been set alight, reported The Guardian, and many local shops along the high road had been broken into. Haringey Council said the damage to roads and pavements in Tottenham was in the region of £227,000, according to the Daily Mail in 2011.

Speaking on the morning of 7 August, Lammy described the events as a “disgrace”. “What happened here on Thursday night raised huge questions and we need answers”, he said. “The response to that is not to loot and rob… This must stop. This is an attack on Tottenham, on people, on ordinary people.”

Unrest spreads across England

The day after the Tottenham riots, televisions showed “helicopter shots of rioting across London”, writes Oliver in The Times. “From Hackney to Croydon, Ealing to Bromley, shops [were] on fire or being looted.” It was agreed that Prime Minister David Cameron, who was on a summer holiday in Italy, should fly back as soon as possible. Then-Mayor of London Boris Johnson was criticised for not coming back from his holiday quickly enough.

“These images of rioters driving the police from the streets quickly proved an inspiration to others”, says Matteo Tiratelli, a lecturer in political sociology at University College London, in The Conversation. Over the next five nights, roughly 15,000 people took to the streets in towns and cities across England. “Hundreds of police officers were injured and £250m worth of damage was done to shops and businesses in London alone.”

On the evening of 8 August, the riots claimed two lives: Trevor Ellis, 26, was found with bullet wounds in a car in Croydon and Richard Bowes, 68, was critically injured trying to put out a fire. He later died from his injuries.

Two days later, on 10 August, Haroon Jahan, 21, Shazad Ali, 30, and Abdul Musavir, 31, were killed when a car hit them in Winson Green, Birmingham. According to witnesses, they had been protecting their community and local businesses from looting and destruction.

Hours after finding his dying son in the street, Jahan’s father called for calm: “Black, white, Asians – we all live in the same community... step forward if you want to lose your son. Otherwise, calm down and go home – please”, he said.

An extra 1,700 police officers were deployed in London and more than 400 people were arrested. “The Met was stretched beyond belief in a way that it has never experienced before,” Stephen Kavanagh, the Met deputy assistant commissioner at the time, told BBC Breakfast. It is thought that social media networks including Twitter and BlackBerry Messenger played a key role in fuelling the unrest.

Although protests over Duggan’s death had sparked the original Tottenham riots, many seemed to agree that the unrest was “a long time coming” and not just a reaction to the shooting, The Telegraph said. One woman told the paper: “You had a tinder box that was waiting and that was just the match… It's frustration by young people who have been pushed to the wall.”

How did the riots end?

By 11 August, the total number of arrests in London had reached 1,009 and of those, 464 people had been charged. One hundred families had been made homeless as a result of the unrest, five people had died and 26 police officers were injured. The situation was reaching a tipping point and, by the fourth night of the riots, London increased its number of police to 16,000 by pulling in officers from other forces across the country.

This greater police presence on the streets was the major factor in persuading people to stay at home, according to the Reading the Riots study, which interviewed 270 people involved in the events.

“I think the 16,000 police was a deterrent for everyone; they thought: ‘You know what, we’ve done enough, we’ve done what we had to do… Leave it’,” said one of the people interviewed, a 23-year-old unemployed man from Newham, east London.

Other explanations for the riots ending included a lack of excitement and there being nothing left to loot. Some of those involved in the report said they were impacted by Jahan’s father’s moving speech. “When I [saw his] interview I did stop like, because that did hit me quite hard”, one interviewee said.

The aftermath

The IPCC’s investigation into Duggan’s death continued, but in September 2011 Duggan’s brother Shaun Hall said he was “not confident at all” that the watchdog would successfully establish what had happened, the BBC reported.

That same month, Scotland Yard apologised to Duggan’s family for failing to inform them directly of his death. A year on from Duggan’s shooting, in 2012, his mother, Pam, said she still had “no answers about why my son died”.

To this day, questions remain surrounding the events which led to the shooting. In 2015, an IPCC report “found Duggan was probably in the process of throwing away a handgun when he was shot”. However, Forensic Architecture, a human rights research organisation based at Goldsmiths, University of London, has said this conclusion is wrong, according to a detailed report in The Guardian published in 2020.

The IPCC has called “implausible” a claim that police moved the gun. “There is no sensible reason why they [the police] would have opted to plant the firearm on the grass such a distance away from Mr Duggan thereby giving rise to the various doubts which have inevitably arisen about this matter,” the police watchdog said.

The penal response to the rioters was “enormous and unprecedented”, says Tiratelli on The Conversation, with cases “pushed from the magistrates’ to the crown courts, ensuring that longer sentences were available and costing minors their right to anonymity in the press”.

The result was that more than 2,000 people faced jail sentences “which were four and a half times longer than those same offences would normally warrant”.

In 2011, Cameron agreed to establish the Riots Communities and Victims Panel to investigate the causes of the riots and consider what more could be done to build greater social and economic resilience in communities.

A decade on

Only “a handful” of the 63 recommendations in the After the riots report have been implemented, writes David Lammy in The Guardian, which included “calling on the government to provide greater support for families, address youth unemployment, improve school attainment, improve police relations and tackle reoffending by young offenders”.

Over the years, “instead of acting to strengthen the fabric of society’s fire blanket to reduce the risk of riots”, Conservative prime ministers have “decimated police forces, youth services and local authority budgets”, he adds. “I say this with deep regret: by failing to implement the measures designed to tackle society’s dissatisfaction, alienation and fragmentation, Johnson risks letting a spark set fire to the fuel all over again.”

But writing in The Times, Oliver says he believes that if the country faced a similar situation again, “the police would be quicker off the mark in terms of tightening their grip and making clear actions have consequences”.

However, the events of 2011 made it clear that “social order isn’t as stable as we thought”, he adds. “All it takes is for a few thousand people to rebel and, as Yeats famously wrote, ‘Things fall apart... Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world’”.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Kate Samuelson is the newsletter editor, global. She is also a regular guest on award-winning podcast The Week Unwrapped, where she often brings stories with a women’s rights angle. Kate’s career as a journalist began on the MailOnline graduate training scheme, which involved stints as a reporter at the South West News Service’s office in Cambridge and the Liverpool Echo. She moved from MailOnline to Time magazine’s satellite office in London, where she covered current affairs and culture for both the print mag and website. Before joining The Week, Kate worked as the senior stories and content gathering specialist at the global women’s charity ActionAid UK, where she led the planning and delivery of all content gathering trips, from Bangladesh to Brazil. She is passionate about women’s rights and using her skills as a journalist to highlight underrepresented communities.

Alongside her staff roles, Kate has written for various magazines and newspapers including Stylist, Metro.co.uk, The Guardian and the i news site. She is also the founder and editor of Cheapskate London, an award-winning weekly newsletter that curates the best free events with the aim of making the capital more accessible.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

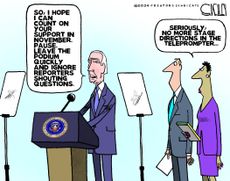

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Will Aukus pact survive a second Trump presidency?

Will Aukus pact survive a second Trump presidency?Today's Big Question US, UK and Australia seek to expand 'game-changer' defence partnership ahead of Republican's possible return to White House

By Sorcha Bradley, The Week UK Published

-

It's the economy, Sunak: has 'Rishession' halted Tory fightback?

It's the economy, Sunak: has 'Rishession' halted Tory fightback?Today's Big Question PM's pledge to deliver economic growth is 'in tatters' as stagnation and falling living standards threaten Tory election wipeout

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

Why your local council may be going bust

Why your local council may be going bustThe Explainer Across England, local councils are suffering from grave financial problems

By The Week UK Published

-

Rishi Sunak and the right-wing press: heading for divorce?

Rishi Sunak and the right-wing press: heading for divorce?Talking Point The Telegraph launches 'assault' on PM just as many Tory MPs are contemplating losing their seats

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet, The Week UK Published

-

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?

How would a second Trump presidency affect Britain?Today's Big Question Re-election of Republican frontrunner could threaten UK security, warns former head of secret service

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'

'Rwanda plan is less a deterrent and more a bluff'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published

-

How the biggest election year in history might play out

How the biggest election year in history might play outThe Explainer Votes in world's biggest democracies, as well as its most 'despotic' and 'stressed' countries, face threats of violence and suppression

By Harriet Marsden, The Week UK Published

-

'Good democracies include their poorest citizens. The UK excludes them'

'Good democracies include their poorest citizens. The UK excludes them'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By The Week UK Published