The chemtrails conspiracy: what are the claims?

Theorists believe governments, big businesses or the UN may be behind a large-scale secret plot

In the right weather conditions, long lines of thin clouds trailing planes can be seen in the sky, sometimes long after an aircraft has disappeared from view.

These clouds are contrails, and are the result of water vapour emitted from planes condensing in freezing temperatures, leaving behind “thin trails of ice crystals”, explained the Met Office.

But “ever since the US Air Force published a paper in 1996 about the hypothetical harnessing of weather for military objectives”, a “shadowy global aviation conspiracy” has spread among online communities, said National Geographic.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Theorists’ beliefs

The chemtrail conspiracy theory took root in the 1990s, but in recent years “a significant number of people” have taken to social media to share “speculation, questions and images of contrail cross-hatched skies”, said the BBC.

“Believers” say that the “puffy plumes of water vapour” that trail from planes are “evidence of a secret plot to control weather or poison the environment” by spraying chemicals into the atmosphere, the broadcaster continued.

A common claim is that the emissions from a standard plane should “dissipate quickly so any clouds that do not disappear immediately must be full of additional, undisclosed substances”, said Scientific American.

Depending on theorists' individual beliefs, “a pick-and-mix selection of the UN, the military, national governments, the Rothschilds, climate scientists, pilots and big business” are claimed to be responsible for chemtrails, said the BBC.

The reasons why a large organisation might be behind this kind of activity span a range of “nefarious purposes from weather modification, to human population control via sterilization, to even mind control”, added Scientific American.

A survey conducted in the US, Canada and UK in 2011 found that “an incredible” 16.6% of respondents subscribed to the theory, said National Geographic. A 2017 paper published in Nature found that percentage could be as high as 40% among the US general population.

Scientific response

Scientists have maintained that there is no evidence of chemical substances being atmospherically spread via planes in order to alter weather patterns, or to poison or control humans.

A common claim made by believers is that chemtrails can be distinguished from normal contrails “because they remain in the sky for longer than they did prior to the mid-90s, and dissipate into cirrus clouds”, said National Geographic.

The Met Office explains, however, that once ice crystals have formed, “what happens next depends on how dry or how humid the air is”.

In dry air, ice crystals will turn from a solid to a gas “and become invisible”, says the weather service. But in humid conditions, the emitted water vapours “will stay where they are, often spreading out, leaving a fluffy trail where the aircraft has passed”.

Trails of ice crystals “may last for many hours, leaving the sky criss-crossed with lines”.

The evidence

A paper published by Environmental Research Letters in 2016 collated 77 experts’ conclusions on evidence of a “secret, large-scale atmospheric program” (SLAP). The authors noted that public confusion or uncertainty about the chemtrail claims may have been in part due to the scientific community having not addressed these concerns rigorously for some years.

All but one of the scientists that took part in the study said they found no evidence of a chemtrail plot. The one anomaly was a scientist who recorded an unusually high level of atmosphere barium in a remote area where ground soil contained low levels of the chemical element.

However, “to get from that one result to the idea that we’re being secretly sprayed with chemicals requires a monumental leap of faith”, said the BBC.

The scientists concluded that data used as evidence by chemtrail theorists “could be explained through other factors, such as typical contrail formation and poor data sampling instructions presented on SLAP websites”.

The authors noted that the public’s concerns about health, climate change and pollution were “reasonable”, but focusing on a large-scale spraying programme “may be taking attention away from real, underlying problems that need addressing”.

Going mainstream

National Geographic describes the chemtrail theory as “a load of codswallop”, but it appears to have “gone mainstream” nonetheless. The 2016 study “did little to convince hardcore believers”, said the magazine, and believers “dismissed” evidence that the theory isn’t true by claiming it is “part of a massive cover-up”.

The BBC has attributed the proliferation of the chemtrails conspiracy theory to its resonance in certain digital communities. “Closed groups of like-minded people – the type common on social media and the internet – are one of the big reasons why conspiracy theories solidify online,” the broadcaster said.

“The conspiracy theorists won't be swayed.”

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Julia O'Driscoll is the engagement editor. She covers UK and world news, as well as writing lifestyle and travel features. She regularly appears on “The Week Unwrapped” podcast, and hosted The Week's short-form documentary podcast, “The Overview”. Julia was previously the content and social media editor at sustainability consultancy Eco-Age, where she interviewed prominent voices in sustainable fashion and climate movements. She has a master's in liberal arts from Bristol University, and spent a year studying at Charles University in Prague.

-

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'

'Horror stories of women having to carry nonviable fetuses'Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

By Harold Maass, The Week US Published

-

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn in

Haiti interim council, prime minister sworn inSpeed Read Prime Minister Ariel Henry resigns amid surging gang violence

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

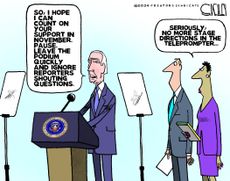

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 26, 2024Cartoons Friday's cartoons - teleprompter troubles, presidential immunity, and more

By The Week US Published

-

White Easter more likely than a white Christmas

White Easter more likely than a white ChristmasTall Tales And other stories from the stranger side of life

By Chas Newkey-Burden, The Week UK Published

-

Alex Jones admits Sandy Hook shootings were real

Alex Jones admits Sandy Hook shootings were realSpeed Read Infowars founder has been ordered to pay $4.1m damages to parents of boy killed in the attack

By The Week Staff Published

-

Experts play down speculation of ‘secret passageway’ on Mars

Experts play down speculation of ‘secret passageway’ on Marsfeature And other stories from the stranger side of life

By The Week Staff Published

-

The teenage gorilla with an addiction to smartphones

The teenage gorilla with an addiction to smartphonesWhy Everyone’s Talking About Amare, the 16-year-old ape, has screen time cut after spending ‘hours’ looking at visitors’ phones

By The Week Staff Published

-

‘We need to reassess our toxic relationship with flying’

‘We need to reassess our toxic relationship with flying’Instant Opinion Your digest of analysis from the British and international press

By The best columns Published

-

Alpha Men Assemble: the group threatening ‘direct action’ over vaccines

Alpha Men Assemble: the group threatening ‘direct action’ over vaccinesWhy Everyone’s Talking About The anti-vaxxers claim to be fighting for ‘justice, equality and freedom for everyone’

By The Week Staff Published

-

London’s sad Christmas tree

London’s sad Christmas treeWhy Everyone’s Talking About This year’s annual festive gift from Norway fails to wow social media users

By The Week Staff Published

-

Who will replace Andrew Marr at the BBC?

Who will replace Andrew Marr at the BBC?Why Everyone’s Talking About Four of bookies' top five favourites to fill his shoes are women

By The Week Staff Published